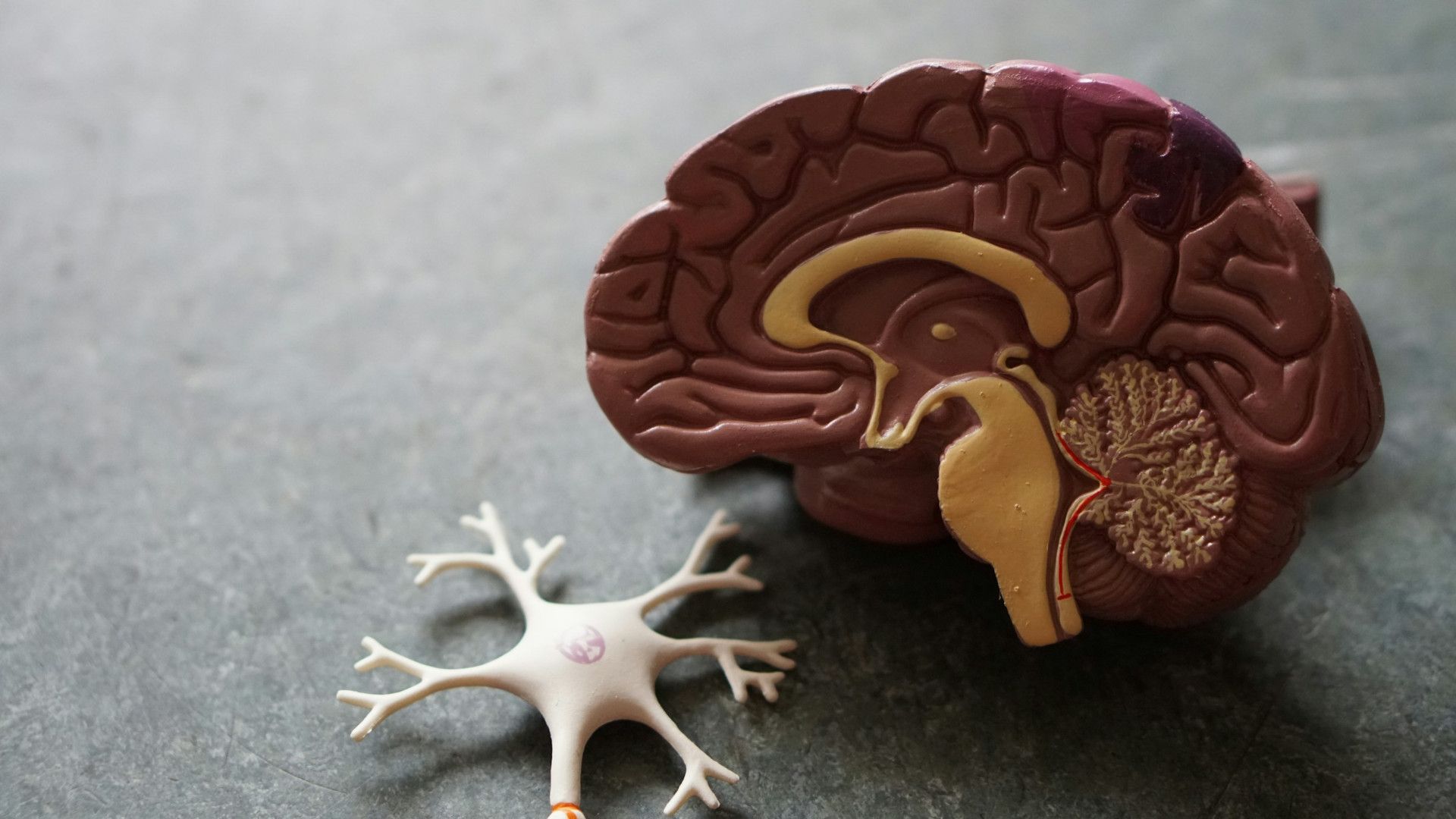

The Nervous System - how we're wired

The knee-jerk part

Animals have a survival mechanism that kicks in when they are in danger. It works quicker than thought and takes control whether we like it or not. According to its assessment of our chances of survival it moves our physiology one way or another. In fight/flight our guts, muscles, heart and senses are brought to high performance levels with hormones such as adrenalin. The decks are cleared for action and anything unnecessary is jettisoned. Soldiers going into battle may soil themselves: there’s nothing voluntary about it. In freeze the muscles shut down and we are immobilised so that any animal predator will stop attacking us.

There are two problems for modern humans:

- Daily life is full of low-level stressors which keep our system half-primed for long periods.

- These mechanisms can’t tell the difference between real life and the cinema in our heads. Anxious thoughts and catastrophising will trigger physiological changes too.

If you’ve been subject to abuse or violence you may look back and ask, “Why did I react like that? Why didn’t I do x or y?” The answer is that the survival mechanism made its best guess and didn’t consult your thoughts or your long-term interests.

When danger is past and safety is restored, the mechanism shuts off, and the modern part of our nervous system comes back on line. If the danger is still present, safety is never restored, and the alert body never relaxes. This leaves people trying to manage a hyper-vigilant state on a daily basis.

The part with choices

Our ability to make thoughtful choices, form allegiances and make decisions based on moral judgements is a more recent evolutionary development. This part of our functioning can only be up and running when the survival mechanism judges it is safe to stand down. To make good decisions and enjoy life we need this modern part to be operating.

A person is a person because of another person

- Shona saying

It is understood that our bodies learn their patterns of regulation in infancy, via bodily contact with a primary carer. Think of how a distressed baby, cradled by its mother, gradually returns to a state of calm. Without such soothing a baby’s body cannot learn this pattern. Thankfully, in later life there are experiences that can make up the shortfall - good friendships, learning to trust a partner, counselling.

The nervous system in counselling

Counselling takes account of the way our nervous system is wired.

Dan Siegel coined the term Window of Tolerance to describe our optimal state, in which we respond to our environment flexibly and enjoy life. When too alerted we are in a ‘hyperaroused’ state and our body wants to fight or run away. When shutdown we are in a ‘hypoaroused’ state where our body wants to collapse and make itself invisible. These states are not a choice, they just take over. Sadly, some trauma survivors experience these states frequently or all the time.

Stephen Porges has formulated the Polyvagal Theory which proposes that ‘neuroception’ monitors the environment all the time, below the level of awareness. The autonomic nervous system evolved in a hierarchy:

- the earliest ‘dorsal vagal’ system uses a strategy of immobilisation

- the next ‘sympathetic’ system adds fight and flight

- the most recent ‘ventral vagal’ system offers safety through connection with others. When this state is active, body and brain work together and processing and change are possible.

Co-regulation is a biological imperative. It is essential for survival. The ability to self-regulate is built on ongoing experiences of co-regulation. Through co-regulation we connect with others and create a shared sense of safety.

- Deb Dana

The first stage of counselling for trauma is to teach how to recognise and regulate physiological states. This is sometimes enough in itself. Please see counselling for trauma